Inside a Mythbusters origin story with Adam Savage

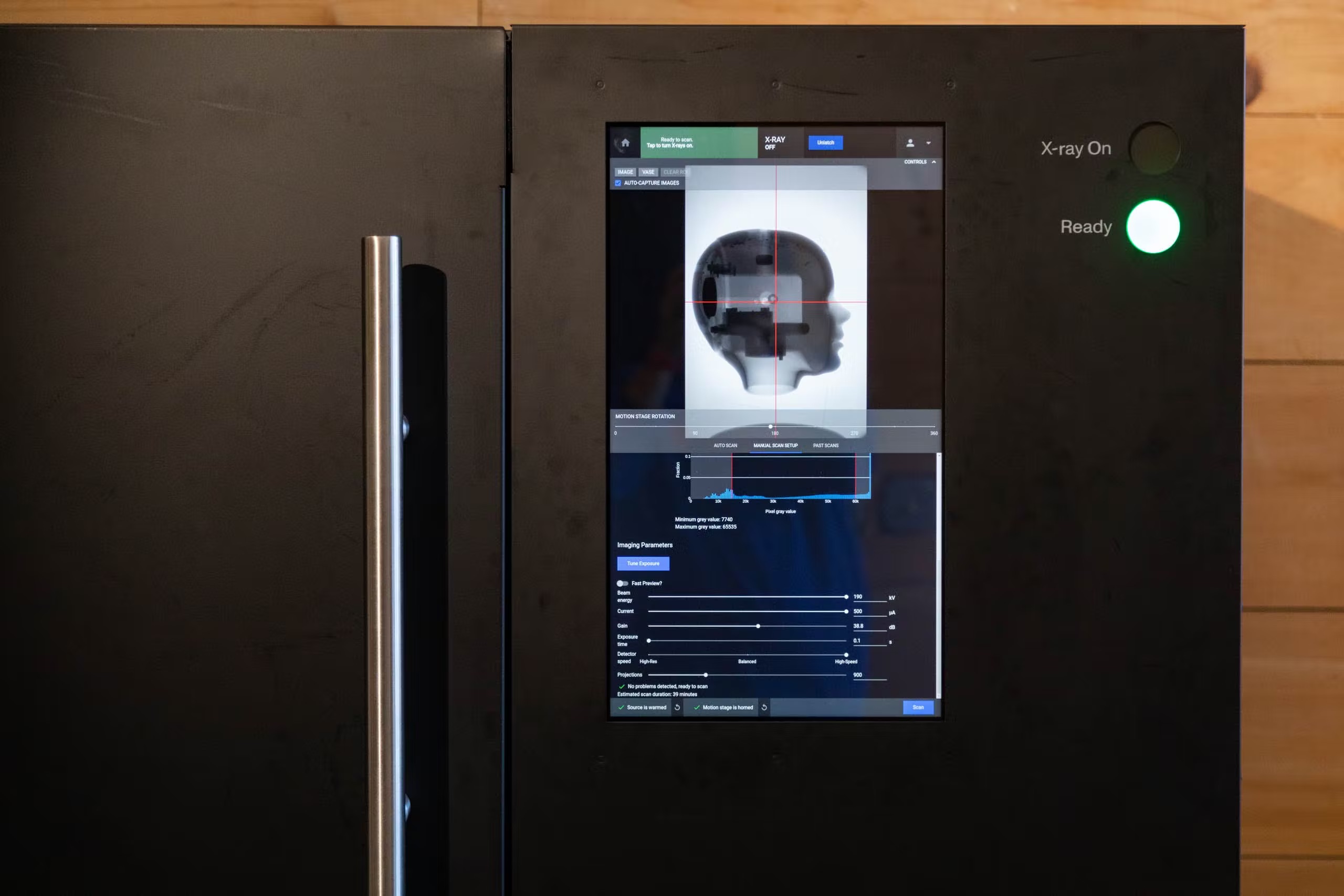

Adam Savage and the Tested team dropped by Lumafield’s San Francisco office once again, this time to use our Neptune industrial CT scanner to excavate a Mythbusters origin story.

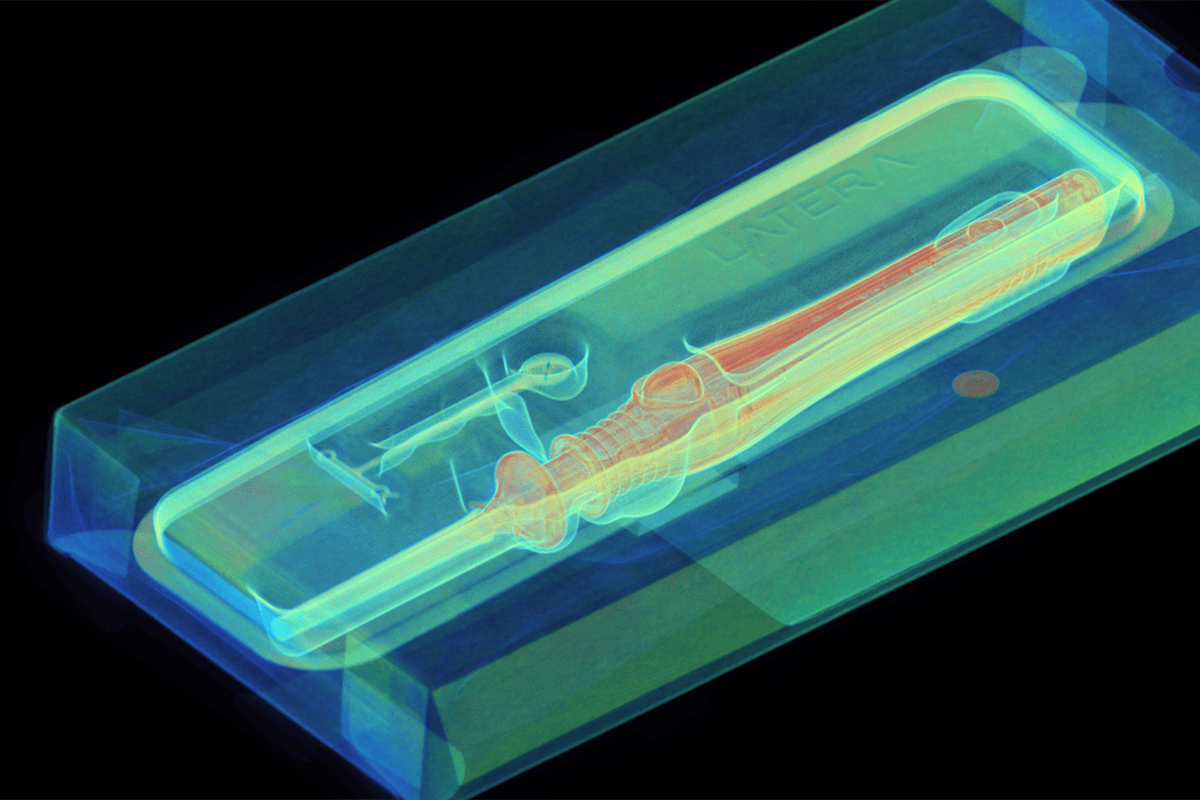

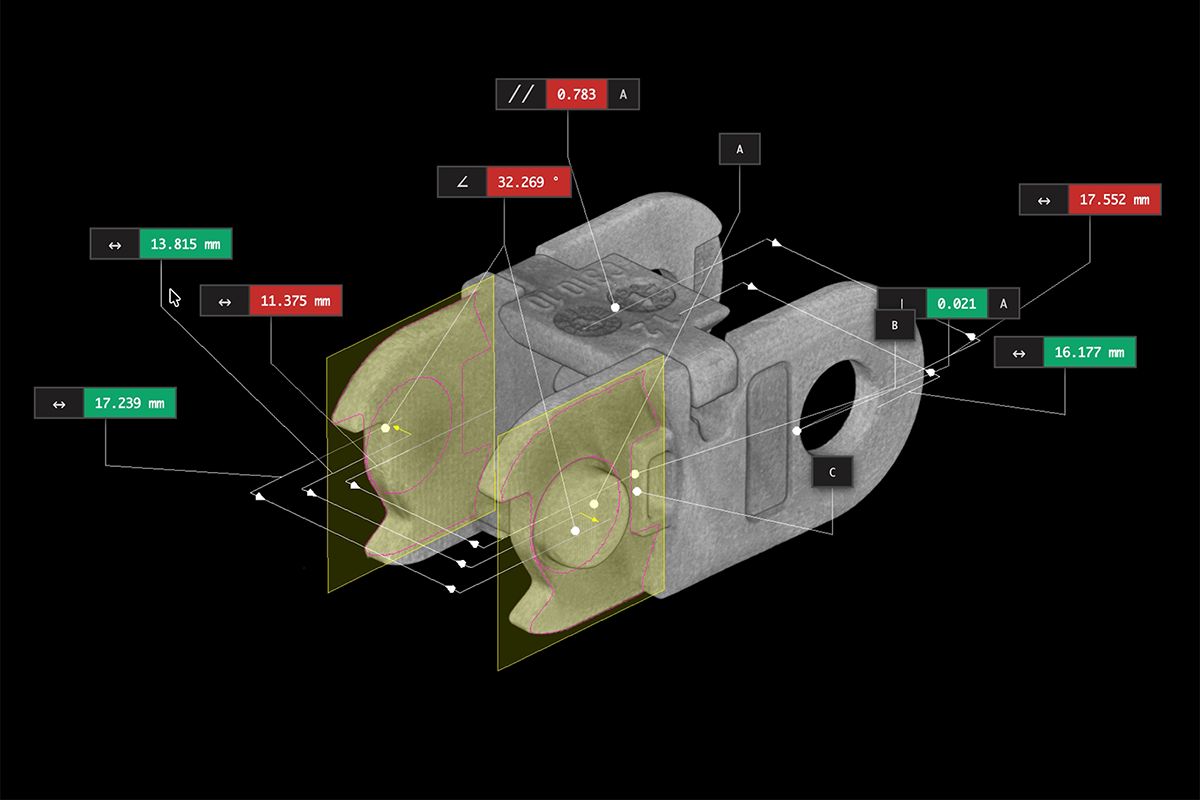

Our Voyager software combines thousands of x-ray images taken from different angles into a 3D model that allows us to see an object’s structure—both external and internal. Engineers rely on our technology throughout the design and manufacturing process to perfect their products—everything from lithium-ion batteries to medical devices.

Buster, the “sixth host” of the original Mythbusters—after Adam, Jamie Hyneman, Tory Belleci, Kari Byron, and Grant Imahara—is a Hybrid II crash test dummy designed to measure human reaction to automotive impact. He survived untold abuse and damage over the course of 10 years on the show, beginning with an initial drop from 170 feet when he withstood 700 G of force (seven is enough to kill a person).

“This might be the grossest thing I’ve ever CT scanned” is really saying something coming from Lumafield CEO and co-founder Eduardo Torrealba. Eduardo walked Adam through scans of Buster’s hand and face, then turned to the tech hidden inside a modern crash test dummy. At the end of the episode, Eduardo hands over a special memento: a 3D printed rendition of Buster's face, created from our CT scan, that captures features as small as his improvised stitching.

With CT scanning, we can isolate materials and peel back the vinyl on Buster’s hand to see the steel “bone” underneath. More than the difference in densities between these component parts, our software allows a glimpse at the dummy's manufacturing process, which has changed surprisingly little since the 1970s. A slice view shows exactly how the two elements interact when clamped together.

Buster’s face, though not a complex mechanical assembly, still tells a story. Adam recalls how Kari Byron sewed the stitches that kept Buster together; with CT, you can see underneath them to fully appreciate her craftsmanship. Crowning Buster’s head is a compacted spot of higher density—evidence of just how many times he’s been dropped on his head.

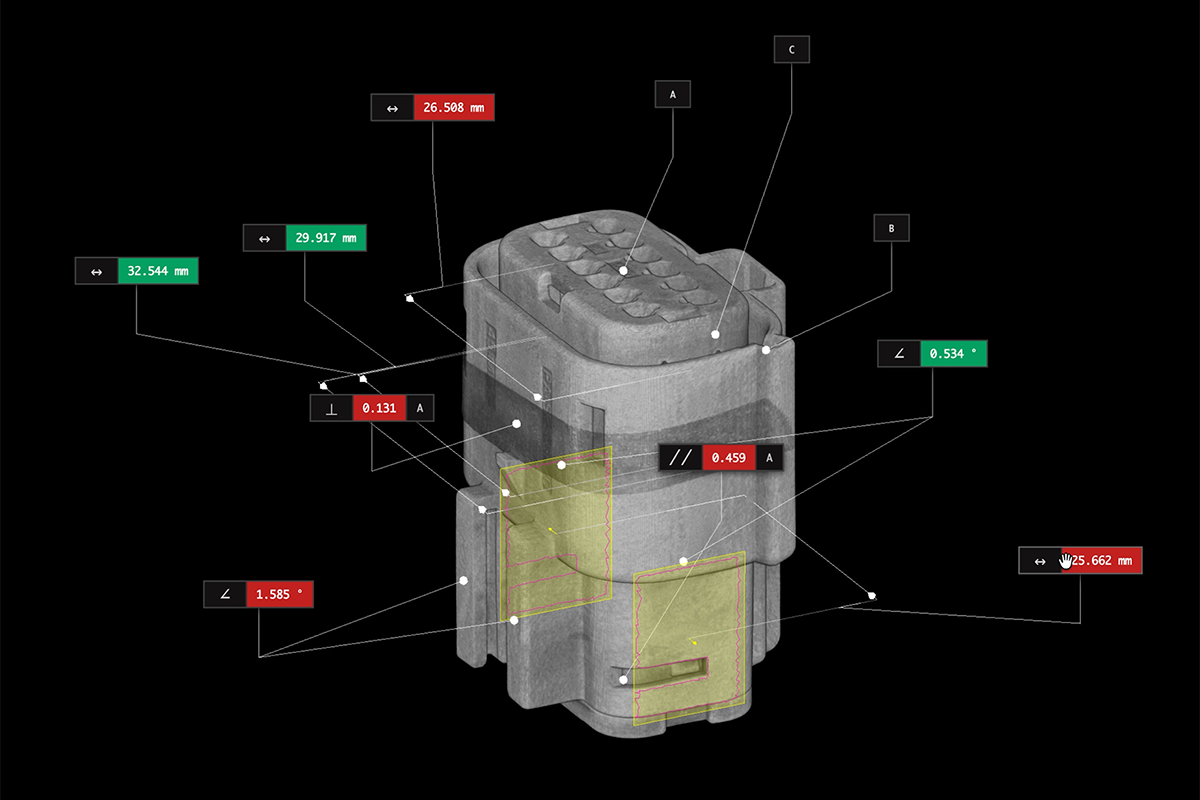

Adam also shared the small head of a child crash test dummy, an analog to a 10-year-old. Inside a plate on the back of its head, you’d typically find a transducer to measure impacts—likely using a wheatstone bridge with four resistors. In this instrument, three legs of the bridge have set resistance values, but the fourth is a variable resistor. By measuring the change in voltage across the circuits, you can determine how much force the head endures during impact.

The way Eduardo and Adam examine these components is a lot like how our customers use the Neptune scanner. They want to know if they’re positioning sensors correctly, if their fasteners are screwed in the right way, and if their molding processes are sound. Industrial CT gives engineers the confidence to know exactly what’s there, even down to the smallest stitch.

As a parting gift, we brought Buster back to life. Having extracted STL models from our scan, Eduardo presented Adam with a pair of highly detailed 3D prints of Buster, scars and all. You can learn more about the process of getting from CT scan to 3D print here.

Engineers working on everything from performance athletic equipment to consumer packaging would agree with Adam when he says that “every time I’m looking at one of these scans, it gives me insight.” If you’re interested in exploring how industrial CT can help you develop this unparalleled insight into your application, contact us!